The Artists

Tiyan Baker is an artist who works with installation, photography, video and sculpture. Her practice draws on historical research, language, digital processes and material play to trace unseen relationships between words, place and stories. Centring her Bidayǔh culture in her works, Baker is also interested in things she has unknowingly inherited. Living far from native lands, culture and family, in the midst of the (re)colonisation of Borneo, she explores all that can be mistranslated or lost, and what can manifest in its place. She has shown her works widely across Australia, and is the winner of the 2022 National Photography Prize awarded by the Murray Art Museum Albury. She was born and raised on the Larrakia lands known as Darwin and currently lives and works on the Awabakal and Worimi lands known as Newcastle, Australia.Loren Kronemyer is an artist living and working in remote Lutruwita / Tasmania. Her works span objects, interactive and live performance, experimental media art, and large-scale worldbuilding projects aimed at exploring ecological futures and survival skills.

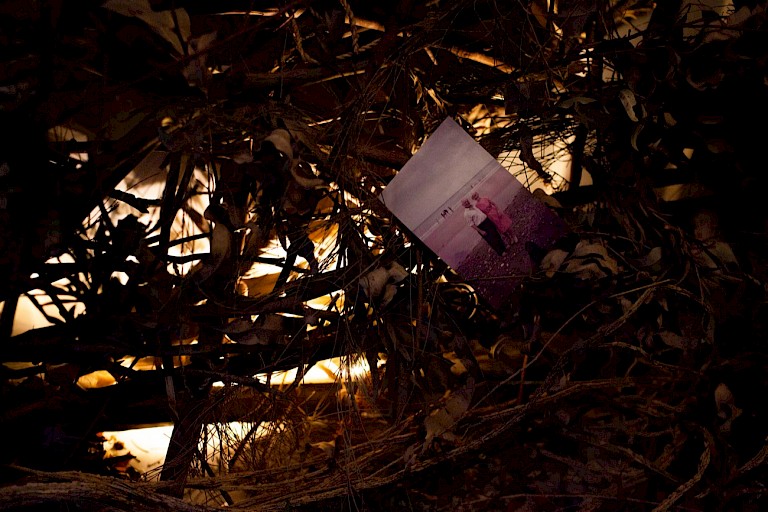

“We both decided to collaborate together based on our common experiences exploring online channels concerning the ideology known as doomsday prepping. Both of us shared a lot of complex feelings of fatalism around the future, both identifying with and critiquing the broader cultural tools we had to discuss and deal with those feelings. We are both contemporary artists, Tiyan with a practice in video and digital media and Loren with a practice of installation and performance. When The Big Anxiety festival in Sydney put out a call for several commissioned works, we took it as the opportunity to collaborate on an idea that captured our observations about climate anxiety.” (Baker and Kronemyer)“The topic known as climate anxiety covers a lot of nuanced emotions. Since we made the project in 2017, a lot of this discourse has moved to the forefront more. At the time we created the project, we both were following a forum known as the Near Term Human Extinction Support Group. In that forum, people would post about a wide range of topics, from real-time updates about weather disasters around the world or in their communities, to small, deeply-felt, troubling observations about flowers blooming unseasonably early. In our communities in Australia, it varied widely how attuned our friends and neighbours were to climate change. Via this project, we took the opportunity to also work with an Australian philosopher called Glenn Albrecht, who has been working for many years to coin new words to describe what he calls “earth emotions”. These include words like “solastalgia”, which means the melancholy we feel over the loss of our home environment. These are examples about how climate anxiety manifests among ourselves, our friends, and our local and global communities.” (Baker and Kronemyer)“I define “solastalgia” as the pain or distress caused by the ongoing loss of solace and the sense of desolation connected to the present state of one’s home and territory. It is the existential and lived experience of negative environmental change, manifest as an attack on one’s sense of place.” (Albrecht, 2019, p. 38)The Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht believes that anthropogenic climate change and its global impacts on the natural environment have generated “global emotional upheaval,” with experiences of climate anxiety or solastalgia increasingly widespread in contemporary society. Apocalypse Anonymous was an immersive public art installation exploring these concepts and experiences in a public park in Sydney, Australia.Baker and Kronemyer came together to collaborate on Apocalypse Anonymous out of a shared interest in exploring online doomsday-prepping communities. Neither are strangers to experiences of climate anxiety and solastalgia.Installed in Parramatta Park as part of the Big Anxiety Festival 2017, Apocalypse Anonymous features three immersive environments in containers which suggest different ways of coping with climate anxiety and distress. The artists describe these environments as follows:“The first environment represented the experience offered by online fora, which can be a gateway, intensifier, or support system for apocalyptic thinking. In this room, we featured a desktop computer which hosted a bespoke program that scraped together a variety of posts from several online fora. Users could sit at the desk and explore the messages and videos on this program. We curated posts that we thought represented the variety of ways people shared their apocalyptic feelings online. After a couple of years of research and planning, by the time we made the work, we were already seeing an intensification of disastrous weather events associated with climate change. Many of the people we connected with online had gone from speculating about preparing for disaster, to living through it.The second environment represented total preparedness. Participants entered a bunker-like shelter, which contained the amount of recommended rations for a natural disaster, a bed, and other supplies. On a solar-powered radio, you could hear interviews with people in Australia who practised preparedness or had survived recent natural disasters. We wanted to explore what happened when online speculation moved into real, lived experience.The last environment encapsulated the feeling of ambivalent acceptance towards ecological change. It was filled with rich, composting mulch, which was dotted with numerous prints of nostalgic analogue photographs of families and loved ones living their lives. A recording of our personal interview with Glenn Albrecht, conducted on his farm, played in this space, where he outlined how he understood and coped with earth emotions like solastalgia. Participants could settle into this space and embrace the possibility of uncertainty, decomposition, and the fact that we all progress together towards the inevitable fate of matter.”

Climate anxiety is a topic and experience with increasing relevance for populations around the world, not least those in low-lying coastal areas whose futures are disappearing under rising sea levels. According to a recent global study, children and young people across all countries are worried about climate change, with 59% being extremely worried and 84% moderately worried (Hickman et. al., 2021). One of the strengths of Apocalypse Anonymous is its emphasis on the emotional dimensions of our sense of place, specifically, our dis-ease or even our sense of homelessness in today’s urban environments. “The title for this project is a play on the names of support groups, imagining a support group for the experience of being mid-apocalypse.” Like good therapists or “schizoanalysts,” Baker and Kronemyer do not provide easy answers in this support group but rather trouble us to lean into and work with the experiences of climate anxiety or distress and to find our own way through.The artists provide a compelling symptomatology of Anthropocene society (an analysis of its conditions as symptoms connecting the interpersonal and the social/ecological). We are reminded here of the Nietzschean proposition, taken up by Deleuze (1990), that “artists are clinicians, not with respect to their own case, nor even with respect to a case in general; rather, they are clinicians of civilisation” (p. 237). Elsewhere, Deleuze (1967) even suggests that artists can go further than doctors and (conventional) clinicians in symptomatology because “the work of art gives them new means” (p. 13). The new means of public art, in this case, reside in the performative and speculative dimensions of Apocalypse Anonymous, which mediate our emotional relationship with time and place and offer new tools with which to make sense of the contemporary world and the feelings and impulses that exist in a continuum between the personal and the planetary. Climate anxiety isn’t an experience for which there are always the right words. One of the tools offered by this project (and Albrecht’s philosophy) is the gift of new words for the world unfolding before us, confronting as this future may be.